A Link to the Mountains

Learning to climb in the Gunks often begins with instruction on belaying, anchors, and ethics which inevitably leads to stories about the two most influential pioneers of the region, Fritz Weissner and Hans Kraus. These early pioneers brought with them from Europe the skills and techniques of roped climbing, but it was their beginnings as mountain climbers that would leave an ever lasting impression on the Gunks.

Today, many within the climbing community of the U.S. view the Gunks as a trad-climbers stronghold, a place where bold routes were done ground up and onsight. However it also has the reputation of being stodgy, unable to change with the times, and a place for grumbling old-timers, holdouts from an era of antiquated ethics. Whether your views are traditional, modern, or perhaps a mix of both, the culture has been deeply shaped by the climbers who came here first and the method by which they established their routes.

In a bit of a climbers game of Seven Degrees of Separation it is likely that if you have climbed with a variety of partners in the Gunks you have probably roped up with someone who has climbed with Rich Romano, who in turn climbed with John Stannard, who climbed with Hans Kraus and Kraus with Fritz Weissner. Within each of these links the climbing partnership acts also as an apprenticeship in which views, goals, and aspirations are shared and taught. These links in the Gunks share strong ties with mountaineering.

Photo of Hans Kraus courtesy of John Rupley.

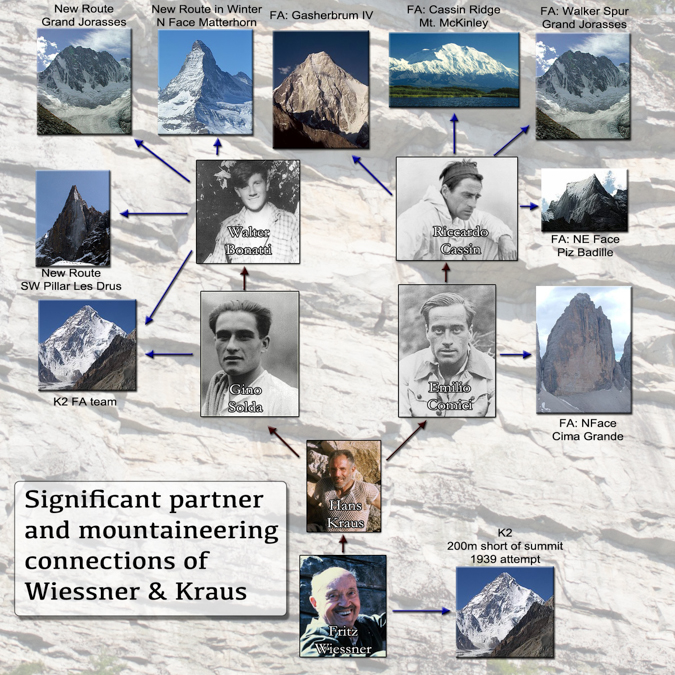

Weissner himself came within 200m of summiting K2 in 1939, fourteen years before the first ascent. Kraus's background was no less tied to mountaineering. One of his principle early partners was Gino Solda who was part of the first ascent team of K2 and he routinely teamed up with Emilio Comici who's protege Riccardo Cassin climbed Gasherbrum IV. Solda in turn climbed frequently with Walter Bonatti whose partners Miche Vaucher, Kurt Diemberger and Hermann Buhl climbed the first ascent of Broad Peak, which was also the first alpine style ascent of an 8,000m peak. Buhl later went on to solo the first ascent of Nanga Parbat which had claimed 31 lives before his successful ascent.

So what are we to make of this connection? In our current day, climbing has splintered into so many disciplines that it is hard to see the link between a boulderer working a single move on the carriage road and a mountaineer pushing through a storm high on an icy face in the Himalaya, but by tracing the history back to the earliest Gunks climbs that link becomes clear. Rock climbing in the 1930's was often seen as an exercise in developing skills for the great mountain ranges of the world rather than an activity enjoyed solely for it's own experience.

In Weissner's own words, "The Shawangunks not only offer an excellent opportunity to the climber who wants to practice for future goal in the high mountains, but to many of those in the eastern United States who are not able to travel far they constitute a wonderful mountain world of their own."1

The technically hardest moves in their pure form will always lag behind the technical standards set on local cliffs where the encumbrances of the mountains are rarely encountered. However each discipline adds to the whole and appreciating these connections help bind us as a community of driven individuals seeking to find our own understanding of the world. Without this history we lack the lens enabling us to see our own actions objectively.

[1] "Early Rock Climbing in the Shawangunks," Appalachia, June 1960, pp. 18-25.